Research Review: Psychological Adjustment During COVID-19

As we surpass the 6-month mark of the COVID-19 pandemic, some people’s lives are affected to a small degree while others are facing serious social, emotional, and/or health challenges. For all of us, there is uncertainty with no clear “end date.” A key task during the pandemic has been, and will continue to be, minimizing distress and maximizing resilience. Resilience refers to the ability to mentally and emotionally cope with a crisis, such as COVID-19. With this in mind, people have started to ask: “What can we do to build and maintain resilience over the long-term?”

Several research studies have highlighted the negative impact of COVID-19 on wellbeing. Initially, researchers conducted “snapshot” studies, which looked at individuals’ wellbeing or mental health at a single timepoint. The U.S. National Pandemic Emotional Impact Report presented results of a nationwide Internet survey of U.S. adults in May 2020 which found an increase in life stress, loneliness, depression, and anxiety in the majority of adults. As the pandemic has continued, researchers have shifted their focus to resilience factors, which have helped people cope as the situation changes.

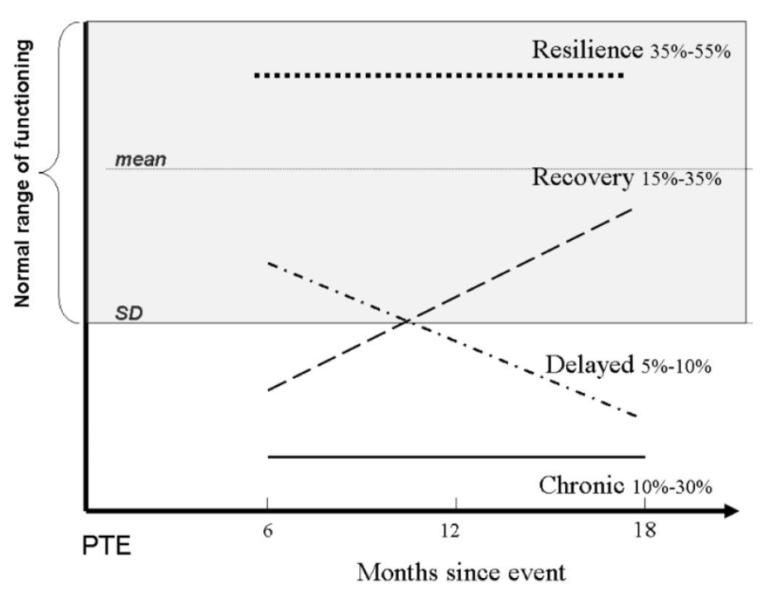

While the challenges presented by COVID are somewhat unique, we can learn from studies conducted during previous outbreaks. One illustrative 2003 study assessed well-being among patients who were hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong. This study looked at patterns of recovery which included the dimensions of physical health, social activity, and mental health. Four patterns of recovery were identified, which did not appear to be solely due to the severity of the illness itself (1):

- Resilience (Minimal negative impact): 35-55% of individuals demonstrated minimal negative change.

- Recovery (Initial negative impact, followed by recovery): 15-35% of individuals had an initial negative impact but then improved.

- Delayed negative impact: 5-10% of individuals initially did not show a negative impact but then showed a decline over time.

- Chronic (Lasting negative impact): 10-30% of individuals had negative impact from the beginning and throughout.

From this study, we know that the majority of individuals affected showed recovery from a similar virus to COVID. Four factors were identified as playing a role in recovery: 1) exposure severity, 2) individual factors, 3) family context, and 4) community characteristics. Individuals who were in the resilient or recovery groups had greater social support and less SARS-related worries, highlighting the importance of other individual, psychological factors beyond the illness itself.

How can we be resilient?

Minimize exposure

- Wear a face mask.

- Avoid touching your face.

- Clean your hands often, either with soap and water for 20 seconds or a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol.

- Maintain safe physical distancing by at least 6 feet from the people around you.

Individual factors

- Stay informed without overindulging in media consumption (e.g., set a limit on how long you will watch/read the news each day).

- Employ staying well techniques (e.g., exercising, reading, practicing mindfulness).

- Reduce isolation by using online communication or by participating in socially distanced and/or using masks in small social gatherings outdoors (e.g., walking with a neighbor).

Family context and social support

- Increase family and close friend cohesion (e.g., develop a constant routine or responsibilities for family/friends which can increase security and increase a sense of meaning, recognize other’s efforts, build new memories with a “electronic-free” night to remove barriers to closeness).

- Communicate (e.g., reach out to friends and family when you are struggling or if you notice they are struggling or isolated).

- Adopt financial management strategies (e.g., create budgets, review and track expenses).

Community characteristics

- Increase the sense of solidarity in the community (e.g., put up an encouraging sign in your window/yard “We’ll get through this,” do something positive for the neighborhood such as pick up trash, plant flowers, put up holiday decorations, volunteer at a local food pantry.)

- Understand health disparities in different communities and encourage policies that strive to narrow the gap.

Any one of these factors has a small impact, so more work should be done to understand multiple factors.

There is a need for flexibility: paying attention to changing situations, deciding on using appropriate strategies to cope, evaluating the outcome of strategies, and modifying if needed (2).

To better understand the impact of COVID-19, research will now integrate resilience factors across individuals, families, and communities across time. Such research will highlight key factors for intervention and identify individuals and communities that are most vulnerable and in need of intervention.

Abigail Wright, PhD

Research Staff & Junior Investigator, MGH COE

References

- Bonanno, G. A., Ho, S. M., Chan, J. C., Kwong, R. S., Cheung, C. K., Wong, C. P., & Wong, V. C. (2008). Psychological resilience and dysfunction among hospitalized survivors of the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: a latent class approach. Health Psychology, 27(5), 659.

- Chen, S., & Bonanno, G. A. (2020). Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: A resilience perspective. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S51