Prevention in Psychiatry: Why Now?

What are “subclinical” psychotic symptoms?

Mental health disorders such as ADHD, depression, and anxiety are routinely screened for in pediatric practices (1), so that children and adolescents who may have these conditions receive the help they need as soon as possible. However, psychotic symptoms that are “subclinical” – that are not severe enough to be considered a true psychotic symptom but are similar in content to a psychotic symptom—are not typically assessed by pediatricians.

This is surprising since these symptoms are relatively common and are associated with an increased risk for developing a range of mental health disorders, such as depression, anxiety and rarely, a psychotic illness like schizophrenia (2). These symptoms include a wide range of unusual experiences, for example: seeing flashes of light that may not be there, hearing sounds that are not heard by other people, feeling that other people are not saying what they mean or have harmful intentions when in reality they do not, or noticing many coincidences or events that seem to have a great deal of personal significance (3). Unfortunately, very limited information is available about what these symptoms in adolescents mean.

How are subclinical symptoms assessed?

One important question about these symptoms that has been debated extensively is: do they need to be evaluated by a clinician, or are they basically normal for many and not terribly worrisome?

Well, it’s complicated. These symptoms are very common in young people (17% in ages 9-12, (4)) and thus relatively “normal”, but they can represent a sign of something more worrisome. This is why we recommend that a child or adolescent who reports these experiences, particularly if the symptoms persist over time, receive an evaluation from a mental health professional.

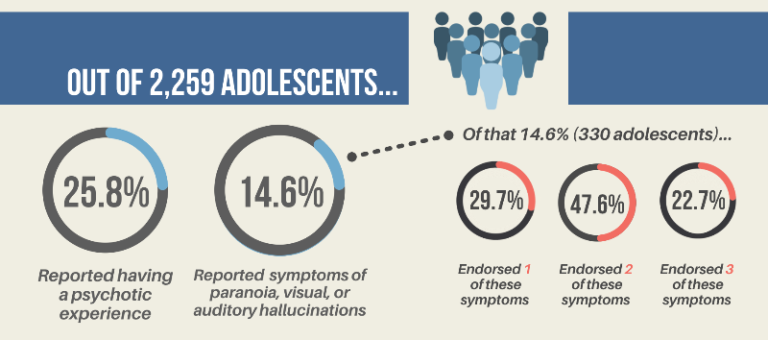

This recommendation is based on our recent research. For the past two years, our programs, the Resilience and Prevention Program (www.resilienceandprevention.com) and the Center for Addiction Medicine (www.mghaddictionmedicine.com), have collaborated to study these symptoms in adolescents. A school-wide mental health survey was conducted in six public middle schools in the Boston area in the Fall of 2019 (and completed by 2,259 students, average age 12.2 years). This survey asked students whether they had experienced seven subclinical psychotic symptoms. Then, 15 of the adolescents who reported these symptoms, but had no history of mental health treatment, completed a 3+ hour diagnostic assessment, with the help of their parents.

Results from our subclinical research survey

We found that 25.8% of the 2,259 adolescents screened reported having at least one of these 7 subclinical psychotic symptoms, and that the more of these symptoms these adolescents reported, the less they were able to effectively regulate their emotions (as measured by an emotion regulation questionnaire (5)). Also, we found that 93% of the subset of 15 adolescents who participated in a full diagnostic interview had a psychiatric condition, with 71.4% having more than one condition. In addition, approximately half of the evaluated adolescents described having suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Lastly, a key finding of this study is that the adolescents’ parents were relatively unaware of their children’s symptoms—the parents’ ratings of their children’s symptoms were much lower than their children’s own ratings.

Results from the subclinical research survey.

This last finding is not entirely surprising given that, during adolescence, it is normal and expected to have less open communication with your parents and not as much monitoring by adults, compared to younger ages. Because of this and their understandably limited knowledge about mental health conditions, parents cannot be solely responsible for assessing the mental health of their children. This is why in-school screening for subclinical symptoms of mental illness is so important. Universal school-based screening for these and other symptoms of mental health conditions can provide a non-stigmatizing way to identify at-risk children early on (similar to the way early problems with reading and math are identified). After they are identified, these children can then receive appropriate treatment or close monitoring if needed, before these types of symptoms lead to mental health problems that can have more long-lasting and harmful effects on their lives.

Authors

Nicole R. DeTore, PhD

MGH Resilience and Prevention Program

Instructor, Harvard Medical School

www.resilienceandprevention.com

Randi Melissa Schuster, PhD

Assistant Professor, Harvard Medical School/MGH

Director, School-Based Research and Program Development, MGH Center for Addiction Medicine

Director of Neuropsychology, MGH Center for Addiction Medicine

http://www.mghaddictionmedicine.com

http://www.idecidemyfuture.org

Twitter Links

@RandiMSchuster | @iDECIDEteam | @mgh_cam

Daphne J. Holt, MD, PhD

Director, Resilience and Prevention Program and Emotion and Social Neuroscience Laboratory

Co-Director, MGH Psychosis Clinical and Research Program

Associate Professor, Harvard Medical School.

References

- Davis M, Rio V, Farley AM, Bush ML, Beidas RS, Young JF. Identifying adolescent suicide risk via depression screening in pediatric primary care: An electronic health record review. Psychiatr Serv. 2021 Feb 1;72(2):163-168. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000207. Epub 2020 Dec 18.

- Poulton R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, Murray R, Harrington H. Children’s self-reported psychotic symptoms and adult schizophreniform disorder: A 15-year longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(11):1053.

- Kelleher I, Harley M, Murtagh A, Cannon M. Are screening instruments valid for psychotic-like experiences? A validation study of screening questions for psychotic-like experiences using in-depth clinical interview. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(2):362-369.

- Kelleher I, Connor D, Clarke MC, Devlin N, Harley M, Cannon M. Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Psychol Med. 2012;42(9):1857-1863. doi:10.1017/S0033291711002960

- Nock MK, Wedig MM, Holmberg EB, Hooley JM. The emotion reactivity scale: development, evaluation, and relation to self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Behav Ther. 2008;39(2):107-116.