Risk Factors for Serious Mental Illness: Not Just “What,” but “When.”

Biological and Environmental Risk Factors

As with most medical illnesses, risk for mental health problems depends both on things we can control, and things we cannot. Primary care doctors tell us that our risk for having a heart attack is increased if we are older, or if we have a family history of heart problems – but also if we are overweight, smoke, or lead a sedentary lifestyle. While we can’t change our age, or our genes, we can eat a heart-heathy diet, quit smoking, and exercise more – and each of these changes has been shown to reduce risk of heart disease, including in people who are at increased risk because of the factors beyond their control.

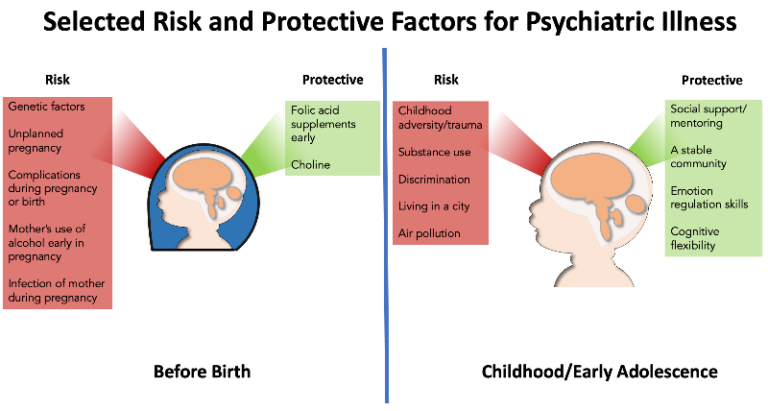

Risk for most categories of mental illness starts with our genetic makeup – which, for now, is not something that we can change, in part due to its complexity. Further, in recent years, many different social and environmental exposures have been linked to increased risk for schizophrenia and other mental health problems – factors such as traumatic or stressful life events, poverty, living in urban environments, migration, and discrimination. These, too, are complex factors that challenging to modify. That being said, as described in Dr. Holt’s article, early identification of those at risk, and early intervention, can result in better outcomes. The more we know about genetic and environmental risk factors, the better the odds of catching someone early in the course of illness, or even before illness begins.

But what about modifiable factors that can actually prevent the onset of mental illness in the first place? Psychiatry lags behind other areas of medicine in primary prevention – in part because when someone develops a mental health problem, similar to when someone develops Alzheimer’s disease, its roots in the brain can begin years or even decades before the onset of symptoms. Knowing when to start looking for these brain changes may lead us to more effective ways to prevent mental illness before it starts.

Prenatal Risk & Interventions

Recent scientific developments make it clear that for schizophrenia and other serious mental illness, brain changes that predispose someone to illness start very early in life – even before birth. For example, our recent work shows that children who were exposed to any combination of maternal tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana use early in pregnancy, or obstetric or birth complications, had a substantially greater risk of significant mental health problems at age 9-10 – including after accounting for socioeconomic factors and adverse childhood exposures.

Selected risk-conferring and protective exposures. Adapted from Roffman JL & Dunn EC. Neuropsychopharmacology reviews 2022 hot topics: the prenatal environment and risk for mental illness in young people. Neuropsychopharmacol. and data from Stilo SA & Murray RM. Non-Genetic Factors in Schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep 21, 100 (2019).

However, just as the developing fetal brain may be especially susceptible to injury, prenatal life may also be an opportune time to intervene, to lower one’s risk of lifetime mental illness after birth. Replicated studies now show that the children of women who start taking folic acid supplements either before conception, or within the first two months of pregnancy, have approximately half the risk of autism compared to children where folic acid was started later in pregnancy. We have reported that protective effects of folic acid may extend well into adolescence, by altering the development of the brain’s outer cortex in ways that counter psychosis risk. Maternal folic acid intake early in pregnancy may be one of many early-life interventions that offset a child’s risk for mental illness.

Through a project called “Brain Health Begins Before Birth (B4),” our team is working to discover, develop, and implement other interventions, potentially including optimizing maternal mental health, prenatal care, physical activity, nutrition, and sleep during pregnancy; family and community-level supports; and other potentially modifiable factors. We envision a time in the near future when addressing these factors as part of primary care can have an impact in reducing mental health risk in young people, as they have for other areas of medicine.

Joshua L. Roffman MD, MMSc

Co-director, MGH Division of Psychiatric Neuroimaging

Director, MGH Early Brain Development Initiative

Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

https://www.b4study.com/